Over the last several months, the world has had to deal with lock-downs, restrictions, and social distancing measures as preventive strategies against COVID-19. With a majority of society staying indoors, ‘normal life’ – be it social gatherings, work, or education – has come to a grinding halt. In the face of these obstructions, people have turned to Information and Communication Technologies to adapt to being home, and to continue functioning as ‘normally’ as possible. While this has been a great switch for people with a stable internet connection and access to technology, it has also left a large population of the world helpless. Those without internet and devices are being left behind, and the COVID-19 pandemic is creating and worsening a new form of social division in society – the digital divide.

Access to digital infrastructure has been shown to differ greatly based on two factors: gender and income. All over the world, and particularly in India, women are less likely to have access to the internet or technology than men. In Bangladesh, for example, 42% males have access to mobile baking, as opposed to a mere 10% of women. Even in a ‘progressive’ and developed country like Singapore, 21% of males have access to mobile money accounts, compared to only 8% of females. These numbers make it clear that the digital divide particularly affects women across the world. This means, therefore, that COVID-19 has made access to work, education, and even socialising tougher for women, due to their relative lack of access.

Similarly, low-income households worldwide have lesser rates of digital access as compared to richer households. This creates problems for a number of reasons. For one, it leads to a form of double discrimination for the female population – women in general are less likely to have digital access, but women from poor income households are even less likely to have said access – because they belong to both technologically marginalised groups.

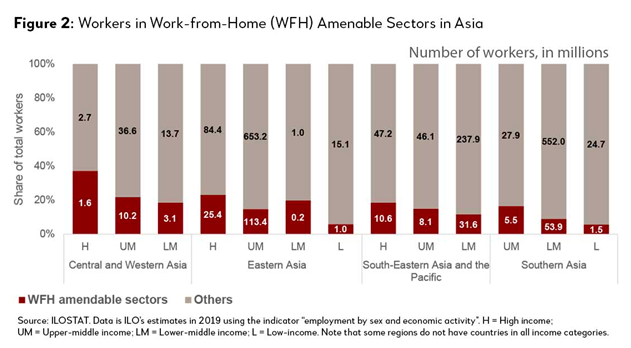

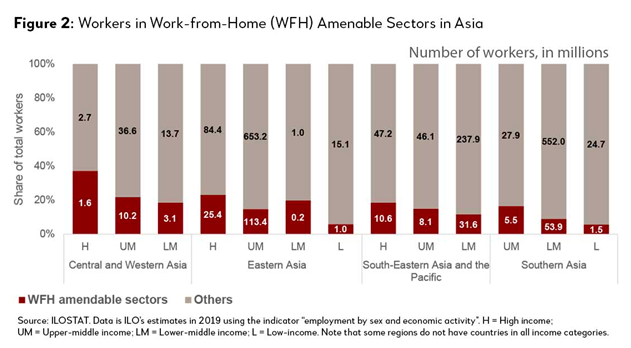

Further, the digital divide has doomed those from poor income households in the employment sphere as well. To begin with, those from low income households are statistically more likely to work in professions that require face-to-face interaction and their physical presence – eg: construction, manufacturing, transportation – jobs that cannot be shifted online. This lack of job flexibility has led to millions of people being let go since they are no longer required in their workplaces – making those who are poor even poorer. To add to this, those from low-income households who are working in sectors that are now working from home have also had to be let go, due to their lack of access to WiFi and technology. The digital divide, therefore, has led to major disruption in the lives of millions of women, and low-income families across the world

COVID-19, therefore, has essentially made both technology and the internet necessary services, without which one cannot secure an income, get educated, or even socialise. This has led to a record high demand for mobile data services in India, since it is easier, cheaper, and more accessible than a broadband connection. The high demand, coupled with the fact that data is a form of an inelastic demand, could mean that data companies could collude – making the most of a pandemic by making profits for themselves. In India in particular, the mobile data market oligopoly (Jio, Airtel and Vodafone), could come together and collectively raise the prices of data services. Considering the internet is now an essential service, such a move would face opposition but ultimately customers would have to comply due to the necessity of the product and the lack of a cheaper alternative. However, this would hurt the digital divide, and the poorest and most marginalised would be worst affected – having to drop out of using these data plans if the prices are raised. This in turn would lead to the same domino effect – lack of access to data leads to lower employment, and the poor therefore getting poorer.

How, then, can the divide be reduced?

To begin with, governments across the world must ensure that such opportunistic and unethical practices, such as price gouging, do not take place – particularly at a time when people are vulnerable. Next, as more activities are moved away from physical settings, governments may be forced to invest more into ensuring that it is indeed possible to ‘work from home.’ This could be in the form of direct provision of goods – for example, the government providing laptops and data connections to students, or by providing subsidies (or even reducing import duties) for tech companies to be able to sell their goods at a lower rate. Governments could also step in by creating access centres – eg computer rooms – for people to be able to come and use or rent desktop screens as required by their employers / institutions.

It is clear that with COVID-19, the reliance on technology, and the lack of access to it, are both increasing, and the digital divide is worsening – particularly affecting women, those from lower-income backgrounds, and those who live in areas with lower connectivity. Those who are already marginalised are now having multiple opportunities taken away from them, and the shift to the online world has only been advantageous for those who can afford it to begin with. It is crucial, therefore, to ensure that those with access barriers do not get left behind, and that governments, technology firms, as well as civil society organisations with grassroots outreach come together to widen access for those who lack it, and ensure that an increased dependence on the digital world does not mean forgetting those who inhabit the real one.